How do you find elk and create opportunities?

It’s a good question, because it’s one thing to find elk, and another to have a chance to shoot an arrow.

Let’s look at some basic strategies for creating shooting opportunities when hunting deer.

First, I’ll have to lay the disclaimer out there: there’s no one answer. There is obviously a myriad of different factors that can affect a strategy for getting into shooting range – from weather and wind, to the location of the elk, to the amount of vocalization, to the time of the year, etc.

But in terms of trying to kill a bull in archery season, there are some general principles that you should be aware of. There are “best practices”, common techniques, and other good things to know. And, thankfully, Jerud and I had the opportunity to prove a few of these concepts last season.

What I want to share in this article is a mix of some common recommendations that I have received from veteran elk hunters, along with the experience that Jerud and I had while killing his bull (putting ourselves in the position to kill multiple bulls, actually).

Let me start where the story started. After several long days of hiking in search of elk, Jerud and I made our way into a new area.

First lesson: cover ground until you find elk.

Don’t spend too much time “tip toeing” around or silently stalking when you don’t know if elk are even in the area. If you aren’t actually finding or hearing elk, you need to get aggressive until you do. This isn’t whitetail hunting.

You can’t kill an elk until you find an elk. Pre-hunt scouting is critical; it can help you determine where to look, but it doesn’t guarantee you’ll find elk. As the oft-repeated phrase goes, “Elk are where they are.”

Second lesson: once elk are located, stop and assess the situation.

Ask yourself questions like… Why are they here?

Where might they be going, and why?

What are the chances that there are more elk than I am seeing/hearing?

What’s the wind doing?

What is the best way to approach the area?

There is a “hurry up and wait” aspect to elk hunting. You need to bust your butt to find them, but once you do, you should stop and assess all of the conditions and variables before making a move.

When Jerud and I sat at the meadow and heard the first bugles, we didn’t rush right after them. We sat for a bit, then cautiously made our way to them until we thought they were staying put for a while.

There’s a fine line to balance here – if you’re too patient then you risk letting the elk move away and potentially losing their location – but if you rush right in without a solid plan, then you might blow them off.

If the elk are moving, try to keep up with them while keeping a safe distance. You want to know where they’re at, but you don’t want them to know where you’re at. Ideally, you want the elk to stop so that you can make a strategic move, which brings us to the next lesson…

Third lesson: get close, then call.

You might have seen a show where a guy calls a bulla half-mile across a canyon – and, yes, that can happen in real life – but it isn’t normal.

Think of it like this. You know there’s a bull on a distant ridge; maybe he responded to a locator bugle that you threw out there.

But why should he cover the ground?

If you’re another bull at a “safe distance”, then you’re no threat. If you’re cow calling from a distance, then he has to be incredibly lonely to come a long way and “get you”.

Now, throw in the fact that he might already have some cows with him, and there’s pretty much no chance he’s leaving his position to challenge a distant bull or bring in a distant cow.

But, if you can close the distance and invade his comfort zone, you’ll get him worked up. Whether you’re calling as a bull (a threat) or a cow (a treat), do it from close proximity and you’re chances of success will skyrocket.

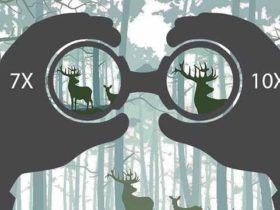

By “close”, I’m recommending within 100-150 yards at the minimum, and ideally within 75 yards for greatest effectiveness.

Distance to elk can be hard to judge if you’re new to hearing wild elk vocalization, and/or you’re hunting in thick timber. Use your best judgment.

In addition to distance, consider the elevation.

If the winds allow it, you want to be at (or near) the same elevation as the elk. And being above them is better than being below them. Like hunting wild turkeys, elk can be more hesitant to approach if they have to move downhill.

If they’re allowed to travel on the same elevation, or come up to the sounds, then their ability to escape is much improved. Use this habit to your advantage.

The second bull that came in silent on me while I was calling-in Jerud’s bull came up a slope, which made it incredibly easy for him to turn around and disappear down the mountainside in a split-second.

The other advantage to approaching from the same elevation is that the winds are typically either coming up or down the mountain, and by approaching from the same level as the elk, you’ll almost always be hunting a cross-wind.

Leave a Reply

View Comments